Rifkin, Not Ripken

Alan Rifkin has represented Maryland’s Senate, governor, jockey club, and, yes, its baseball team.

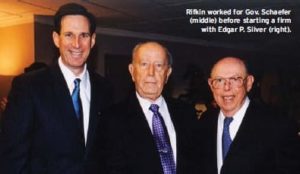

Alan Rifkin grew up in Maryland and graduated from the University of Maryland School of Law in 1982. He spent two years with Semmes, Bowen & Semmes, two years as counsel to the state Senate president, two years as counsel to the governor, and one year at Patton Boggs & Blow before starting his own law firm, Rifkin Livingston Levitan & Silver, in 1989. He spoke with us in late August.

How long have you been outside counsel to the Orioles?

Since 1995.

With a last name like “Rifkin,” which is so close to “Ripken,” have there been any misunderstandings?

[Laughs] I have the good fortune of serving on Cal Ripken’s board of trustees for his foundation and we chuckle about that periodically. There have been times when I’ve called the foundation offices and immediately get through to whomever I’m calling because they think I’m him.

As O’s outside counsel, what do you spend the most time on?

Business operational legal matters and league governance issues. Most sports franchises are pretty substantial business operations.

Example?

Several years ago, Major League Baseball made the decision to relocate the Montreal Expos to Washington, D.C. That decision had substantial and direct implications upon the Baltimore Orioles. For many years, Washington, and the Washington suburbs, were, and are, part of the club’s territory, where tickets were sold and sponsorships were sold, and television markets and radio markets were tended to. So the decision to relocate that franchise had an immediate effect on the club and its operating revenues and opportunities.

How to address it? And how to find that fair balance and resolution that protected and preserved the existing franchise but still allowed for growth and opportunity for the new franchise? The net result of that very intricate series of negotiations with the league, and the Nationals, was the formation of the Mid-Atlantic Sports Network, where the Orioles were, and are, the substantial majority owner- although the Nationals’ interest does increase somewhat over time.

It seems the Orioles got a great deal.

Well, it seems that way, but bear in mind that starting a regional sports network is a daunting task. It took [Orioles owner] Peter Angelos’ vision and fortitude and an enormous amount of work by a number of talented people: seeking and obtaining carriage in dozens upon dozens of cable and satellite networks; going one by one to make sure the product was put on the cable channels throughout that enormous geographic area; and fighting those who had previously held those rights. The club had to weather several lawsuits from cable companies that were disappointed they didn’t have the rights to the Orioles and the Nationals, as they had expected they would get. There were a series of matters that went all the way up to the Federal Communications Commission and broke new ground.

Angelos is a lawyer. Is it easier to represent a lawyer than a civilian, or are they always mucking things up?

I don’t want to make those kind of blanket determinations but I can say this: Peter Angelos is a brilliant attorney. Always has been. I’ve often said that representing Peter Angelos and the Orioles is a little like batting third in a lineup that includes Babe Ruth. It’s nice to have Babe Ruth behind you.

I’m not an Orioles fan but I still have to ask: What happened to them?

My work is on the business side of the sports franchise not on the sports side, so I refrain from giving opinions that are no more than that of a fan. But I think that any fan would recognize that sports are cyclical and all franchises go through certain cycles. The good news is they’ve got a wealth of very talented young players and they’re exciting to watch.

Have you represented other sports franchises?

I was heavily involved in the Washington Redskins’ efforts to relocate the franchise to Maryland during the mid-‘90s. The firm has done work for the Redskins ever since.

How long have you been representing the Maryland Jockey Club?

That’s even longer. Since the latter part of the 1980s.

How did that come about?

I had the good fortune of serving as counsel to Gov. William Donald Schaefer during his first several years in office – at a time when issues related to the Preakness and other racing matters were being heavily debated – and I got to know a gentleman by the name of Frank DeFrancis, who was the then-owner of the Maryland Jockey Club, and had been an international lawyer of great acclaim. A very talented man. Extraordinary vision as to the future of racing.

When I left the governor’s office to go into private practice, one of the first calls I received – if not the first call – was from Frank DeFrancis. He asked me to meet him at 6 o’clock in the morning on the backstretch of the Laurel [Park] race course. When I got there at 6 o’clock in the morning, dressed up in a suit and tie, he sort of chuckled to himself because he was there in work clothes, as anyone would be in the backstretch of a racetrack. And he sat down with me and said, “Before I hire you, which I hope to do, you need to understand this industry. And the place you need to start is right here, where folks are waking up at the crack of dawn to walk horses, train them, and get ready for the day. And if you can understand the backstretch, then one day you’ll understand how this industry operates, and one of these days I’ll let you represent me.”

And for the better part of a year it was a tutelage under the wing of the great Frank DeFrancis. I’m forever thankful.

This seems like a good lead into the referendum on slots in Anne Arundel County. How did you get involved in that?

Obviously, the Maryland Jockey Club’s interests were affected by the potential of a gambling facility less than 10 miles from the racetrack. And we were approached by a group of citizens, who were equally troubled, who believed that the location of the gaming facility was not appropriate to be located at [a] family-friendly mall. They had embarked on a petition drive to place the zoning ordinance to referendum and were anxious to know whether or not the Jockey Club would participate in that process. The Jockey Club said yes, and did, which resulted ultimately in a sufficient number of petition signatures being collected in record time and generated a lawsuit from the now-disappointed potential casino developer. We defended that lawsuit on several occasions, and we were upheld by the Court of Appeals, who found the petition was legally valid and should be placed on the ballot.

You and I are talking at the end of August. This magazine comes out in January. Any predictions for November?

I try to stay away from things outside of my crystal ball. But I do think this: There is an awful lot of passion on the part of the citizenry of Anne Arundel County, and oftentimes passion and community concerns find their way to be successful on the ballots.

What did your parents do?

My mother is a teacher, and has been for three, four decades. Teaches preschool.

My father was in television. He was an engineer and actually turned the lights on – started – the first television station’s broadcast here in Baltimore. When he retired he went after his true calling: He learned how to be a chef. He’s a great chef.

What drew you to the law?

A lot of folks, who are lawyers of my generation, were just enthralled with Atticus Finch. He just seemed to me the epitome of what is right and gracious in the world. And over the years I’ve come in contact with some extraordinary lawyers and people, who cultivated, and helped me cultivate, that interest: Al Brault, Arnold Weiner, Peter Angelos, Don DeVries, Russell Smouse – all students of the law, passionate about handling cases and matters in the right way. They are very detailed, hardworking lawyers who don’t leave a stone unturned. But the most important thing is their respect for the law. It means they also respect the institutions and the litigants. You run across too many lawyers who either don’t respect the institutions or the other litigants.

How did you cross paths with these men?

In a variety of ways. When I was counsel to the governor, I sat on the Maryland rules and procedures committee, and Al [Brault] was involved with that. Many years later, Al was gracious enough to serve as an expert in one of my cases. We’ve had cases against one another from time to time. But most importantly, he was involved in our case with a major cable carrier a time when we were trying to get carriage for the Mid-Atlantic Sports Network.

Don DeVries was my mentor when I first came out of law school, at the law firm I was at: Semmes, Bowen & Semmes. Terrific lawyer.

Arnold Weiner, interestingly enough, was a law professor of mine when I was in law school – that’s how I first met him. He was my trial practice professor. He was a very talented and well-respected lawyer then and more so now.

And you graduated from the University of Maryland law school in…?

In ’82. I was in private practice from ’82 through ’84 at Semmes, and in 1984 I was appointed by the great Mickey Steinberg, who was then the president of the Maryland Senate, to the position of counsel and legislative assistant to the Senate president. I had known [Steinberg] for a while, and had actually interned for him many years earlier when he was a senator on the Judicial Proceedings Committee, and when he was appointed Senate president and the appointing arose for a counsel and legislative assistant he asked if I would take that position. I discussed it with my wife. It represented a 50 percent pay cut.

I was wondering about that.

My wife, to her everlasting credit, said to me that it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and we’ll get by. And we did. It was probably the best decision a young lawyer could make. It was an enormous opportunity. The exposure was almost irreplaceable.

And from that exposure, when Mickey Steinberg was chosen to be the running mate for then-Mayor William Donald Schaefer when Schaefer decided to run for governor, I had the opportunity to meet the soon-to-be governor. When he won the election and needed to appoint a chief counsel and legislative officer, he asked if I would take the position.

Why did Steinberg choose you in ’84?

You know, I never asked Mickey why. I’m almost afraid to ask him. I’m rather glad that I don’t know and delighted that whatever dark moment came upon him to make that decision, he made it.

Any legislation you aided – either with Steinberg or Schaefer – that you think about now?

The first year the governor was in office, we handled the twin stadium bills, the actual funding and authorization for Oriole Park at Camden Yards, and the Camden Yards project. It was landmark at the time to consider that a state government would have the vision to create not one, but two stadia – one designated for baseball and one for professional football – in an urban environment, rather than what had been historically done at that time, which was to place sports facilities in suburbia, causing more traffic and congestion and certainly not invigorating and energizing the urban landscape. It came down to a filibuster in the Maryland Senate.

Edward Bennett Williams – I should have put him on that list [of mentors] – was the owner of the Orioles at the time, and had vowed not to get involved in the day-to-day politics of whether or not the state was going to build or fund a new stadium. He didn’t want to come across as [Baltimore Colts owner] Robert Irsay, or anyone like Robert Irsay, who had threatened the city, and then when his threats went unattended to, pulled up stakes and left. [But] the legislature wanted to hear directly from Williams. And in the end, they were not going to hold a hearing on the legislation unless Williams agreed to come and testify. So it looked like it was going to fail.

Three weeks before the end of the legislative season, Gov. Schaefer, at a press conference, announced that Edward Bennet Williams had agreed to testify and promote the stadium. As soon as that press conference was over, I went back into the governor’s office, and I said, “Governor, that’s terrific news. How did you convince Mr. Williams to testify?” And he looked me straight in the eye and said, “He doesn’t know anything about it. Call him.”

(Laughs.)

So I went back into my office and I called Mr. Williams, who, by that point of the year, was in Florida, attending spring training with the club. He was out on the field and unable to take the call. He did call back, several hours later, and to my good fortune I’m not the guy who picked up the phone; my deputy attorney, David Iannucci, was on the unfortunate receiving end of that elongated blast. To this day I’m not sure if David’s ever recovered.

Did being counsel to the Maryland Senate help when you became counsel to the governor – since executive and legislative branches are often at odds?

It was helpful to me. [But] you do pine away for the inside knowledge of the close quarters of the decision-making in the legislative arena when you’re in the executive branch.

Really?

Yes. It’s a very exciting thing to be involved in the actual dynamic of making law. Then again, it was fascinating to see someone like Gov. Schaefer, who is well-regarded and well-known, here and around the country, and watch how his mind worked to invigorate and empower his cabinet to be creative. His cabinet meetings were always a remarkable event. He would say at just about every one of them that we have no time to waste; we need to be creative now. That’s a perspective that most folks never see.

Any thoughts about Gov. Schaefer’s recent controversies?

Well, controversy generally follows creativity in public policy. When you look at things differently and you address them in different ways, you do so with an eye toward changing the perspective that may have been the present understanding.

You’ve been involved in a lot of cases and projects that take years to come to fruition, but you seem to have the temperament for this. Even the way you talk is measured and specific as if you’re getting ready for a long race.

We have an expression here at the firm, which is well-used: “One of these days, we’re going to do the same thing twice. But this is not that day.”

-Interview conducted and edited by Erik Lundegaard